I’ve just found an old newspaper cutting showing Max Hooper’s obituary, which is also laid out here in this Guardian piece: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/apr/09/max-hooper-obituary.

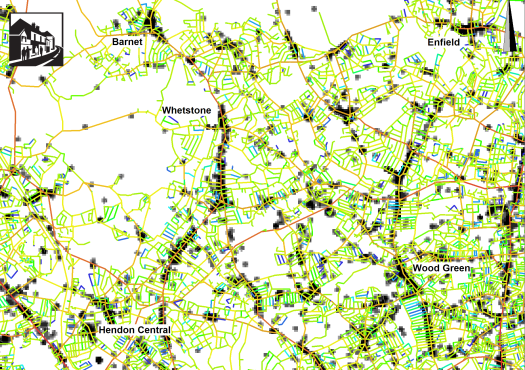

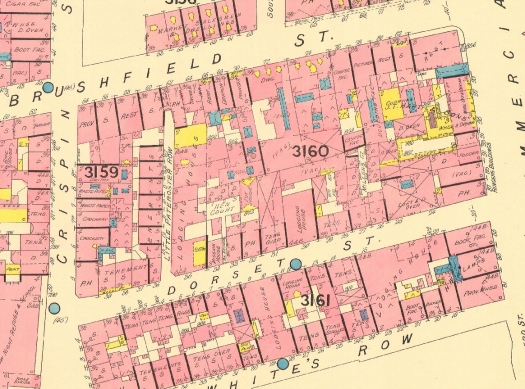

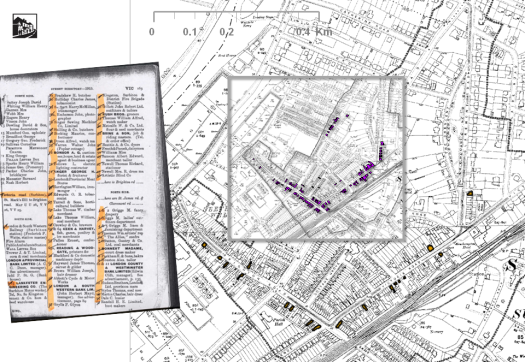

Hooper was an English botanist who devised a system for dating hedges. Starting with a selection of several hundred old hedges, which he dated according to their appearance in old deeds, maps, charters, and the Domesday Book, he counted the number of species in a 30-yard stretch along each of them. He found that the number of tree species correlated with the age of the hedge in centuries and that hedgerows tend to have a much greater diversity of plants and animals and tend to be thicker, taller and more continuous as they increase in age ( this became known as ‘Hooper’s Hedgerow Hypothesis’).

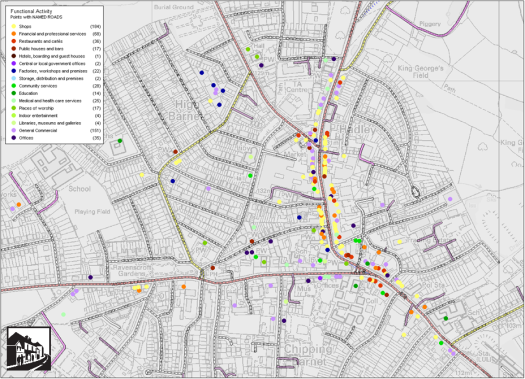

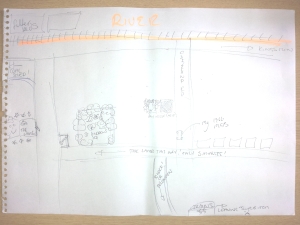

The reason I’m interested in Hooper, is that, thanks to a chance conversation with Professor Julienne Hanson during our suburban town centres research project, when we were puzzling over the significance of land use diversity in the longevity of suburban high streets, we were struck by the possible analogy between high streets and hedgerows. The following is a link to the conference paper, An ecology of the suburban hedgerow, or: how high streets foster diversity over time, which we wrote on the subject.

The paper builds on the proposition by Penn and colleagues (2009) that cities provide a structured set of social, cultural and economic relations which help to shape patterns of diversity in urban areas. Far from being a random mixing, it could be said that urban systems are akin to ecological systems where flora and fauna are closely interrelated and in which the richness and evenness of species in a community contributes to the overall resilience of the ecosystem. This study goes further in suggesting how a variety of building types, sizes and street morphologies are more likely to propagate patterns of co-presence over time – providing the minimal but essential everyday ‘noise’ without which generalised sustainability and liveability agendas are likely to flounder when faced with questions of implementation in particular places. This morphological diversity, it is argued, enables the development of niche markets in smaller centres which can support new forms of socio-economic activity. These ideas were explored further in my chapter called “High Street Diversity, part of Suburban Urbanities: suburbs and the life of the high street (2015).

References

Hooper, Max. 1970. Dating Hedges. Area 2 (4):63-65.

Penn, Alan, Irini Perdikogianni, and Chiron Mottram. 2009. Chapter 11: The Generation of Diversity. In “Designing Sustainable Cities: Decision-making Tools and Resources for Design”, edited by R. Cooper, G. Evans and C. Boyko. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Vaughan, Laura. 2015. Chapter 7: High Street Diversity. In “Suburban Urbanities: suburbs and the life of the high street“, edited by L. Vaughan. London: UCL Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.